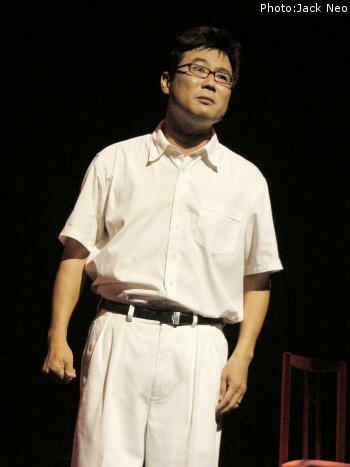

He’s an actor, emcee and comedian but Jack Neo is best known for film- making, and he says it is the result of hard work

He needs no introduction but Jack Neo sure could do with some love and respect from movie critics.

When he arrives for the interview, his latest movie, Love Matters, has just opened in cinemas islandwide.

It has been given a 11/2-star review by this newspaper’s critic, who describes the comedy about the dysfunctionality of love in Singapore as “the usual grab-bag of verbal jokes scotch-taped onto a story that is longwinded, far-fetched and preachy”.

Another review calls it bland and says its “slapstick humour, sexual innuendos and visual gags... fizzle after a while”.

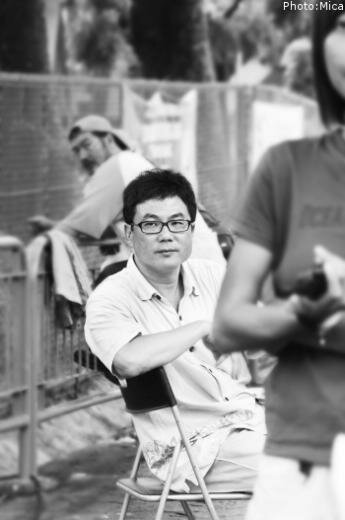

Possibly, the harsh words explain why Neo seems a little ill at ease, perhaps bracing himself for more harsh words about his movie. No sooner does he sit down for the interview than he looks ready to spring from the chair.

“What reporters may not know is that when they write these negative things, we film-makers feel very sad. They say it’s only their personal view but it really hurts a lot of people,” he says.

By his own admission, almost every interview he fields broaches this subject: bad reviews.

By his own admission, almost every interview he fields broaches this subject: bad reviews.

After having directed 11 movies in 10 years, including Love Matters, he is used to the critical drubbing he is always receiving along with healthy box-office receipts. His movies have been called low-brow, predictable, sentimental and didactic.

And he has a well-rehearsed defence: “I’m confident of my movies. I know what my audience wants and I will not sacrifice this to make movies for critics. I want to make movies for people who cannot understand movies, who cannot enjoy Hollywood movies. My shows give them a feeling that is closest to their hearts.”

If Neo so wishes, he could afford not to grant another interview to the media. Although he is friendly enough, he did not become Singapore’s most successful film-maker – with seven entries in the 10 top-grossing local movies of all time – by cultivating friendly relations with the media or by becoming a critics’ darling.

Truly, he is an entertainer of the people and for the people, long before he first saw Eric Khoo’s 1995 feature film debut Mee Pok Man, which got him thinking about making films. “That was the first time I heard about someone making a movie in Singapore – how interesting,” he says.

When Money No Enough, the first movie he was involved in, hit cinemas in 1998, Neo was already a household name, with several careers packed into 20 years behind him.

He had signed on with the army as an infantry officer; got posted to the army’s Music and Drama Company; did part-time acting, emceeing, singing and comedy skits on TV and live theatre and getai shows; conducted drama-training classes; produced karaoke music videos; recorded best-selling comedy albums and published a comic book.

Most significantly, he had a hit Chinese-language TV show called Comedy Night, which had been running for eight years. Heartland Singaporeans loved his salt-of-the-earth, slapstick humour, exemplified by his most memorable comic creations, Liang Po Po, a mischievous granny, and Liang Ximei, a personification of the typical heartland auntie.

It is no hyperbole to say that before he turned 40, he had accomplished more than most others in their entire lives. And after all that prodigious amount of work, he found himself a new career as a film- maker, which secured him the Cultural Medallion in 2005.

Everything he has done, he drew from his experiences as a regular working- class guy. It surprises no one that Money No Enough, which he wrote and starred in but did not direct, is still the most profitable local movie ever, with $5.8 million in box-office takings.

“I know the Ah Peks, Ah Cheks, Ah Bengs and Ah Sengs very well. I’m very heartlander. I performed at getai shows for five years, from 1983, hosting, singing, everything. Because of this, I think I know the problems in our society, what these people think, what they want.

“This is my life. I don’t want to change it.”

Hard-earned luxuries

Three weeks ago, he celebrated his 49th birthday. He lives in a semi-detached house in Pasir Ris with his wife (who helps him in his work) and his four children – one daughter and three sons aged five to 17. His set of wheels: a massive black Toyota MPV.

Such upper-middle-class trappings were not luxuries he was born into; they were all hard-earned.

He grew up in Kampung Chai Chee, the eldest of four children. His father was and still is a fishmonger, manning a stall at a market in Haig Road near Joo Chiat, while his mother works at a coffee shop selling beverages and bread.

“They refuse to retire. They are worried that once they stop working, their engines will slow down,” Neo says.

Formal education for the Tanjong Katong Secondary School boy ended after the O-level examinations. “I got 21 points,” he says, which meant that he did not qualify for junior college or polytechnic. “I passed but I could not go anywhere to study more. I could not stay back either. I was quite lost and didn’t know what to do.”

Formal education for the Tanjong Katong Secondary School boy ended after the O-level examinations. “I got 21 points,” he says, which meant that he did not qualify for junior college or polytechnic. “I passed but I could not go anywhere to study more. I could not stay back either. I was quite lost and didn’t know what to do.”

Since then, his knowledge and skills have been acquired willy-nilly, on the ground as he worked. The phrase he uses to describe his own ad hoc training is “agak-agak”.

How apt. Whether it is acting, hosting, scriptwriting or film-making, he learnt by practice, practice and more practice.

Three years after he signed on with the army, Lieutenant Neo Chee Keong, who had been a quartermaster, then a platoon commander at an infantry unit, was posted to the Singapore Armed Forces’ Music and Drama Company.

What happened was, he had contributed cartoons to Pioneer magazine, published by the Ministry of Defence for its troops.

Intrigued by an officer who was an amateur cartoon artist, Pioneer interviewed Neo and found there was more to him than funny pictures – he had been acting on and hosting TV shows in his free time.

Coincidentally, the Music and Drama Company was looking for a drama director. “My job was to write scripts and train actors. So what I learnt at RTS – that time the TV station was still called Radio Television Singapore – I taught the people at Music and Drama Company.

“During my six, seven years here, I gained a lot of experience in writing scripts and acting because almost every night, we had a performance. It was a very busy schedule. I would write the scripts and rehearse, then watch the shows and learnt what people liked and didn’t like from their response. So that was how I improved.”

‘People’ come first

Indeed, “people” – Neo’s term for popular sentiment – have never stopped shaping his entertainment philosophy. When he performed comedy skits at defunct theatres such as Hoover and Rex and at getai shows, he tweaked his jokes according to the audience’s laugh-o-meter.

“Before Taiwanese singers such as Fong Fei-fei performed, we had one hour to warm up the audience with comedy skits. Very quickly, you knew what the audience liked and didn’t like.

“What I learnt from these live shows trained me to crack jokes every Monday night for 10 years on TV later on.”

He is, of course, referring to the landmark comedy TV series, Comedy Night, which launched in 1990, a couple of years after he left the army, and ended in 2000.

He could just as easily be talking about his movies. Khoo, who in 1999 co-produced Liang Po Po: The Movie which Neo wrote and starred in, says: “Jack definitely knows what works for most Singaporeans.”

Neo’s appeal to the masses, or lowest common denominator, was always good for a hearty chuckle and generally harmed no one until then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong said, in his 2002 National Day Rally speech, that his wife had suggested that Neo should win a national award for his movies, because she enjoyed I Not Stupid, which critiqued the education system.

Thus was a hornet’s nest stirred. The country was divided on whether Neo’s works had artistic merit. Yes, because his films strike a chord with Singaporeans, say his supporters. No, because his movies are a slapdash collection of jokes that betrays a lack of cinematic technique, countered critics.

"If you make a movie thinking about it going to many countries, your burden will be very big..So for me, I just make movies for Singaporeans. Since I am living here, I believe I should understand all the interesting stories around"

Jack Neo on why he produces films on Singaporean culture.

The flames of controversy fanned larger when he received the Cultural Medallion in 2005, a year after getting the Public Service Medal.

Neo will be the first to admit that he is no cinema studies scholar, having grown up on a diet of Wang Sa-Ye Fong comedies on TV and wacky Hong Kong movies such as the Hui brothers’ Aces Go Places series.

“After I saw Mee Pok Man, I thought, ‘Wah, this is called arthouse.’ Before that, I didn’t even know what is called arthouse. I was thinking, ‘How come he would make a film like this?’ I understand the story, but why is it so long, so slow? I didn’t understand it at all.”

But do not equate his lack of formal film training with lazy film-making, he says. “Some people say Jack Neo makes films any old how.

I can tell you, I put a lot of effort into making my films. All my films have a message behind them.

“Giving me the Cultural Medallion is definitely not a mistake. I will continue to work hard to make good films.

“I believe I’m here to make people happy. In the past, on a smaller scale, I did it as a comedian. Now I make people happy in other ways, with my films. That’s why my films have comedy elements.

“But I don’t just want to entertain. I hope my movies can inspire.” Making people laugh is no laughing matter for Neo. He is very serious about his work, says TV actor and host Mark Lee.

Lee, who became Neo’s protege after attending his drama classes in the late 1980s, says: “If you call him in the middle of the night to talk about work, he will talk with you until morning. But if you take him to a shopping mall, he will fall asleep.

“When he takes up a hobby such as cycling, he doesn’t take it seriously. But don’t joke with him when it comes to work. He will scold you. Everything is work with him. His hobby is his work.”

Which is why at any one time, Neo is working on a few projects simultaneously. Like a hummingbird, he appears to be staying put in one place when he is seated for this interview. In reality, his mind is buzzing about other things, even as he juggles calls and messages from two mobile phones.

He says he has about 10 projects in various stages of development, including plans to executive produce a Malay movie. Happily Ever After, his first English-language TV series which he helms as an executive producer, will debut on Okto on March 1.

“I’m like my mother: buay si eh, cannot die,” Neo says of his workaholism. “She won’t sit there and wait for opportunities to come to her. Because we didn’t have much of an education, we treasure every opportunity.”

This article was first published in The Straits Times on Feb 10, 2009.